17 Sep September 11, 1671, 2,000 Warriors Surrounded Hagåtña to free Chief Hurao

Posted at 09:24h

in

Special Forces

by webmaster

Article by: Michael Lujan Bevacqua

September 11, 1671, 2,000 Warriors Surrounded Hagåtña to free Chief Hurao

Every September 11th since September 11, 2001 has a surreal quality to it. As if in a world where history repeats and meaning is always muddled, somehow the events of that day achieved a special, extra level of meaning for those that were alive and of age to experience it. At least this is what they say, and how true this seems depends a lot on your relationship to the US and what type of imaginary tissue connects you to it.

9/11 always means another set of memorial or retrospectives. These commemorative acts help us lock in a particular narrative for conceiving what happened that day, what it means, and whether or not we allow any understanding of events that helped led to that attack. At these memorials people recall where they were when they learned of the attacks and reminders of how scared they were, but how America rose again from those ashes.

Mixed into this naturally is a lot of what you might call blind patriotism or shallow patriotism. September 11th, as the US sees it and many other nations validate is a holiday of American exceptionalism, a site for their feeling of exceptional trauma. So many of the ways that Americans use to describe 9/11 are actually ridiculous. It is as if they imagined they lived in separate universe prior to those attacks and the planes did not just level the Twin Towers but also caused their floating palace to come crashing to the earth.

The years following 9/11/2001 led to a time of leftist self-silencing as liberal and progressive, but not radical elements began to stay quiet for fear of running the façade of patriotic unity and national harmony. Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy, one year after the attacks made the most comprehensive counter to the false logic of 9/11. The way that Americans were insisting that 9/11 be remembered was problematic and dangerous.

Trauma can connect you to others or it can cut you off from others. As an expression of the soul it can valorize the hierarchies of life and make you feel that you should be above others, or that others should suffer and not you, or that other bodies are meant to be the ones that suffer and not yours. As Jacques Derrida argued it was a tragedy, but if you feel it was unique, you can rationalize anything and everything against those who you have marked as being responsible for destroying the pre-traumatic paradise, which of course never actually existed.

In her speech “Come September” Roy talked about other September 11ths in recent memory where terrible things happened in other nations, usually engineered by American intelligence agencies and how far worse periods of atrocities took place in those countries. She did not do this in order to condemn the United States and say simply “What Goes Around Comes Around” or the Chamorro version, “Ti Maimaigo’ Si Yu’us.” She did it as an invitation to welcome the United States to join the world. To stop pretending like it is the duty of all other nations to suffer and starve, while the United States should be isolated from that. Americans should have used that moment in order to perceive the way their privilege has been historically tied to the trauma of others. Unfortunately as we have seen from Bush to Obama, the American exceptionalism that drove the United States to destroy nations from every corner of the globe has been transformed into feelings of exceptionalist trauma, as if nothing could have ever been worse in history than what happened to the most privilege country in the history of the world on September 11, 2001.

I liked the perspective of Roy however in not only to unravel the way Americans were remembering 9/11/2001 and acting as if it was a unique day of trauma in history, but to also remind them of other days in which they were implicated. She reminds the US that they their government was involved in similar 9/11 attacks and tragedies around the world, some of which took place on that fateful date in previous years. I feel that this remembering of history can be important in deflating the dangerous jingoistic and blinding tendencies of how most people commemorate that tragedy.

For me, Guam has its own “9/11” but it takes place long before 2001. It is a day that actually should live in infamy to a far greater degree than 2001. 2001 may have had a significant impact on the world, but in terms of Guam’s history what happened on September 11, 1671 has changed the history the Chamorro people in far more fundamental ways.

It is on this day that the first large scale battle between the Spanish missionaries and soldiers on Guam and Chamorros who resented their intrusion into their lives began. Hurao is a name that is synonymous today with the stirring speech which is attributed to him and the respected Chamorro language immersion group. In response to several injustices including the unfair killing of a friend by the Spanish, Hurao declared emmok against them, vowing to form alliances with other Chamorros and eventually get rid of the Spanish. By the time the Spanish learned of Hurao’s plans he led a coalition that numbered in the thousands. The soldiers protecting the Spanish missionaries became nervous and attacked Hurao’s home, kidnapping him, hoping this would break the back of his army.

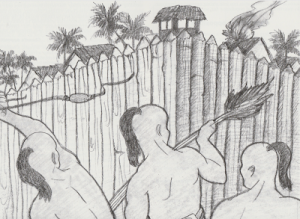

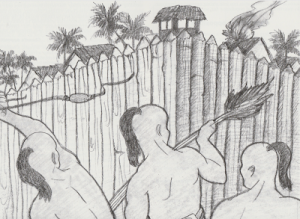

On September 11th, 1671, it is said that 2,000 warriors surrounded Hagåtña with the intent of freeing Hurao and expelling the Spanish. Anticipating the attack, the Spanish had transformed the church and mission into a fort, with canons and towers set up. Chamorros seeing that they had the advantage blockaded the Spanish for a week, surrounding Hagåtña with trenches and emerging from them day and night to mock the Spanish and hurl flaming projectiles in attempt to set fire to their fortification and smoke them out.

It seemed that the Spanish were doomed to eventually be overrun, but Mother Nature intervened to save the Spanish. A terrible typhoon hit the island on September 18th, destroying most of the houses in Hagåtña and knocking down all the trees. The Chamorros, feeling desperate now that their homes and much of their food supply had been wiped out, mounted a full scale assault on the Spanish, hoping that they would not put up much of a fight. The Spanish had weathered the storm fine and were able to fight off the weary Chamorros. The Spanish freed Hurao then hoping it would appease the Chamorros and end the battle. The Chamorros instead attacked again, this time laying siege to the Spanish for nearly two weeks. Once again it seemed as if Chamorros might prevail and eradicate the invaders, but the Spanish in a bold move took the fight to the Chamorros in the trenches. Unprepared for the offensive the Chamorro lines quickly broke and Hurao’s army was scattered.

This was the first of three large scale conflicts which took place during what we today call the Chamorro-Spanish Wars, which lasted for close to thirty years and was fought throughout the Marianas Islands.

Perhaps I am the only one who recalls this part of Guam’s history each September. It wouldn’t be the first time, and it wouldn’t surprise me either. While for many, this is a stretch of their imagination and their rootedness in history and reality. But at the same time, it is an important sort of reminder that our connection to our past is not dictated by a set of temporal rules. The US for example seems to speak passionately, vibrantly and selectively about events that happened hundreds of years ago, and that a gathering of men to sign a document, is alive today as it was back then. This is more than anything meant to caution us on the histories we accept as our own, they channel our energy and lead us down certain paths in the past and certain teleologies in the future.